Written by attorneys Ann Butenhof and Judith Bomster

Click here for a printable version of this article.

Overview: What is Transition Planning and Why Is It Important?

As a parent or guardian of a child with special needs or disabilities, you’ve meticulously planned and provided for your child’s educational and care needs. Then, one day, it hits you. All too quickly your child is a teenager on the cusp of adulthood. What does life look like as your child enters those adult years? The answer will depend heavily on how you and your child plan for that future. The plan you put in place to address the need to transition to life after school will take careful thought and depends heavily on a thorough assessment of your child’s strengths and goals. The sooner you and your child start envisioning their future, and the best path to make it a reality, the better you both will sleep at night.

Your child has already faced and conquered many important life milestones. Arguably the most important milestone for students with disabilities is the transition from school to adult life. It also is arguably one of the most complex and challenging milestones a student will ever face. A carefully conceived and written transition plan, incorporating aspects of education, career, living situations, healthcare, governmental benefits, financial goals and resources, services, and supports, will be an invaluable tool for navigating the complexities of making these major life decisions.

A comprehensive transition plan should address these key areas:

- Education & Career

- Living Situation

- Decision-making

- Healthcare

- Public Benefits (SSI / SSDI / Medicaid)

- Legal & Financial Implications

In this guide, we will cover these major transition plan areas, providing resources and additional information to help you navigate the process of putting together a workable and effective plan. Yes, the task of transition planning can be daunting. But by taking it one step at a time and starting as early as possible, you can focus on each element at your own pace and develop a plan that will give you the peace of mind of knowing your child’s best interests are protected.

For more on this topic, click to read: Your Child Is Growing Up. Planning for Adulthood when your Child has Special Needs.

Early Planning: The Teen Years

Throughout their school years, a special needs child hopefully has had the benefit of strong family, school, and program support, including an Individualized Education Program or Plan (IEP). In most states, including New Hampshire and Massachusetts, individuals are considered adults when they reach the age of 18, regardless of their individual capability to make independent decisions and meet their own needs. They also face “aging” out of their eligibility for federal aid and services through the Individuals with Disabilities Act (IDEA) at the age of 21 or 22.

Recognizing these upcoming milestones, if your child has an IEP, Federal Law requires the IEP to include transition planning as soon as the student reaches the age of 16. That said, there is significant benefit to beginning the planning process with a child even earlier as it takes time for a life plan to fully come together. Understanding your child’s wishes and identifying the supports available to achieve maximum independence and realize life goals will be central to the ultimate success of any plan.

Transitioning from School to the Next Stage

(Note For Students with IEPs [Individualized Education Program or Plan]:

The public school system likely has served as a major coordination hub connecting you and your child with essential resources up to this point.

As your child “ages out” of the public school system, Federal law requires the IEP to include transition planning as soon as the student reaches the age of 16, so you may have already begun this process with your child’s school and/or case manager. Whether you are currently in the planning phase or are anticipating it, this guide can be a helpful tool to use in navigating that process.)

WHAT TO CONSIDER UPON YOUR CHILD COMPLETING SCHOOL

A solid transition plan should address considerations and resources for your (now adult) child’s future education and career options (if these are things your child will be pursuing). Below are key items to discuss with your child and case manager and to include in your plan.

Continuing Education after Graduation

- Will your child be pursuing additional education? If so, will it be in the form of college, trade school, or a job training program?

- Is a high school diploma or GED (high school equivalency) part of their future plan? Will additional education be needed beyond what they have already completed in school in order to attain that educational goal?

- Will they require assistance in making decisions about their education and/or need the support of an advocate on their behalf?

- How will education expenses be covered? Financial aid, ‘gifts’ from family members, and even income from part-time work can have an impact on benefits such as SSI/SSDI, Medicare/Medicaid, and others.

Transitioning from School to Work

- If your child will be able to work, whether part-time or full, what resources will they need to be able to successfully compete for a job?

- Will they require assistance in making decisions about their work and/or need the support of an advocate on their behalf? >> see: Guardianship

- How will their income and future earning potential affect their eligibility for benefits such as SSI/SSDI, Medicare/Medicaid, and others?

Transitioning from School to a New Living Situation

- Will your child continue to live with you or will independent living be a central or future goal of the transition plan?

- If the goal is for your child ultimately to live independently, determining to what degree your child is or can become capable of performing certain fundamental self- support functions such as cooking, using public transportation, and managing money will be important in evaluating this option.

- Will your child benefit from residential services offered through a government assistance program, and is there currently a wait time for such services?

Considerations for College

The journey to get to college is often both challenging and rewarding for a student with disabilities. Navigating an educational system that simply wasn’t built for them is a tremendous feat in itself.

If your child’s next step after graduation is to head off to college, this can be intimidating in the best of situations. What will this next phase of life look like? What supports will be available? Will public benefits your child has come to rely upon continue? How will your role change as your child enters adulthood? While every situation is different, there are some things every family of a child with special needs should consider before driving up to campus on move-in day.

Do a needs analysis:

- Talk with your child about what life and learning will be like in a college

- Identify what supports currently in place will need to continue and whether additional supports might be needed.

- Consider the supports you personally provide at home for daily living and how those could be best managed at school.

Know the benefits picture:

If your child is receiving federal or state benefits, such as cash or medical assistance, there may be changes once your child turns 18 and leaves home for school.

Now is a good time to research and understand:

- The eligibility criteria of any benefits your child may need while at school

- Any assessments that may be required, and the deadlines for submitting applications or required documentation.

Understand the resources available on campus:

There is a significant shift of the support dynamic for children with disabilities at the college level. While you and the school played key roles in proactively managing your child’s secondary school education through an IEP (Individualized Education Plan) or a 504 plan, colleges work directly with students on a reactive basis (i.e., the student generally is required to request support). Although colleges are not subject to the Individuals with Disabilities Act that high schools are, they do fall under the Americans with Disabilities Act designed to ensure equal access and protect individuals from discrimination. Accordingly, almost all colleges have additional services for students with learning, attention, and other disabilities, but these are often not well-publicized.

In order to access services or get needed accommodations, your child will need to register separately with the school’s disability services office. (Accommodations might include note- takers, audio recordings, use of a laptop, or different testing arrangements.)

Consider information access:

When a child turns 18, he or she is considered a legal adult which shifts access to and authority over medical, financial, and educational records from parents to the child.

Empower your student and create an action plan:

The ability of a student to self-advocate can spell the difference between success and failure. Helping your child to understand that, once on campus, the burden for requesting and advocating support will rest primarily on them, and providing assistance in devising a workable plan to obtain that support, will be key.

For more on this topic, read our blog post: Supporting Your Child with Disabilities in College

Guardianship – What Is It, and Do We Need It?

Your child will always be your child, but how you care for them in their childhood years cannot be a lifelong plan as they mature and age out of school and benefit support. An important assumption for the crafting of any transition plan is the consideration of whether your child has or will have the capacity to make decisions about his or her own medical care, education, and finances.

After years of care and protection, one of the most difficult challenges ahead might be supporting or even encouraging your child to embrace and exercise some level of independence as they enter adulthood. This is a time to set aside your own feelings and take a fresh look at your child’s desires and capabilities. What course you both decide to pursue will take careful thought and exploration of all alternatives, including supported decision making (if available in your state) in lieu of full guardianship.

POWERS OF ATTORNEY, GUARDIANSHIP, AND SUPPORTED DECISION MAKING

There are varying types and degrees of guardianship and powers of attorney, based on the particular needs of the individual and their support system. Supported decision making is a newer model that can work with POAs and other documents, and is becoming increasingly popular. Below are highlights of a few of these options that tend to apply to individuals with special needs as they transition into adult life.

Powers of Attorney (POA): In all cases, a power of attorney may be executed by a legal adult (the principal) who is capable of understanding the terms of the document and consequences of signing. The purpose is to appoint someone who makes decisions on their behalf (agent) over specific or broad areas as outlined in the POA. The principal retains the power to revoke the document or discharge the agent (unless it is a surrogacy arrangement — see below).

- Financial Power of Attorney (FPOA)

- A FPOA may be drafted to provide the agent with broad authority over the principal’s finances, or it can be limited in scope. If a FPOA is “durable” it means that the document remains valid even if the principal loses mental capacity in the

- Durable Power of Attorney for Health Care (HCPOA)

- A HCPOA allows named individual(s), referred to as agent(s) or attorney(s)-in-fact, to make health care decisions on an individual’s behalf. An HCPOA becomes effective only when “activated” or when a physician or advanced practice registered nurse certifies in the medical record that the patient is not capable of making or communicating decisions regarding medical treatment.

- (Note: In New Hampshire, a “living will” is a separate section of the HCPOA document, and may be executed at the same time as the If signed, a living will provides more direction to an agent, surrogate or medical providers regarding certain end-of-life decisions.)

- Educational Powers of Attorney

- Educational powers of attorney are power of attorney documents that are more limited in scope and allow the agent to become a substitute decision maker for the individual, assisting them with decisions related to school, such as filling out financial aid documents, advocating on their behalf with school administrators or instructors, and providing support as needed with education-related issues.

- Surrogacy (for health care decisions)

- If a patient loses capacity to make health care decisions after the age of 18 and there is no individual with legal authority to make health care decisions (for instance, the patient never executed an HCPOA), a physician or advanced practice registered nurse may identify a surrogate from a statutory list of prioritized eligible individuals (such as a parent, child, sibling, ). A surrogate may not be appointed over the patient’s objection and the surrogate’s authority terminates after 90 days.

Guardianship: A guardianship is a permanent arrangement that is established by petitioning a court and is considered an adversarial process with representation of both parties, placing the burden of proof on the petitioner. The petition must set forth factual examples within certain parameters that show the individual’s health or safety would be at risk without the guardianship. Only the court can dissolve a guardianship.

- Guardianship of the Person

- Guardianship over the person provides the appointed guardian with decision making authority over areas such as health care, education, and living

- This is the most all-encompassing form of control over an individual requiring the court to legally determine that the individual’s health or safety would be at risk without the As an adversarial process that is not initiated voluntarily by the individual, it should not be entered into lightly.

- Guardianship of the Estate

- A guardian of the estate is necessary if an individual over the age of 18 has assets in his or her own name and requires assistance with managing personal assets. If the individual’s sole asset flows from a monthly check through the Social Security Administration, a family member or interested individual may apply to be appointed Social Security Representative Payee, thus often avoiding the need for guardianship over the estate in certain A person appointed as guardian of the estate most likely will be required to obtain a corporate surety bond, and will be required to file an inventory and annual accounting of assets with the court overseeing the guardianship.

Supported Decision Making: Supported decision making (SDM) is a newer model that allows the individual to maintain control over their affairs while building a network to help that person make and communicate important health, financial, or educational decisions. This is an alternative to guardianship through which individuals may make their own decisions, with support from people they trust, without the need for guardianship.

- SDM can work together with legal instruments such as powers of attorney and release of information SDM is intended to allow the individual a measure of autonomy over their lives while being able to access support from people whom they personally select and trust. This trusted circle of supporters can help the individual better understand what they need to know to make their own decisions regarding medical, financial, and health care needs. Supporters named in an SDM arrangement may also act as interpreters and communicate on behalf of the individual as needed, with the individual still making all of their own decisions, even if they are not able to directly communicate their wishes.

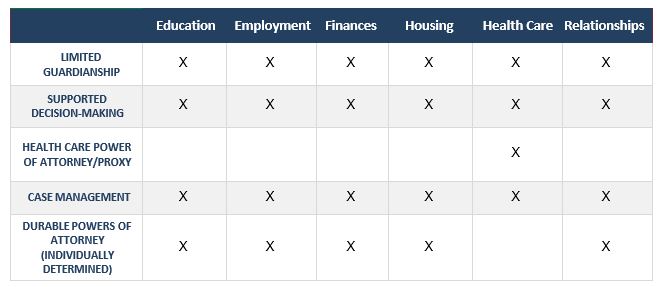

ALTERNATIVES TO FULL GUARDIANSHIP

Some alternatives to full guardianship that can preserve at least some of the legal decision- making rights of the person with a disability are:

Source: Habib, Dan. intelligent lives | OPENING DOORS Guardianship / Supported Decision-Making. Aug. 2021. Presentation.

REAL-LIFE EXAMPLES – GUARDIANSHIP, ALTERNATIVES, AND DECISION MAKING

When considering the ways in which you can support your adult child, and the needs they may have now and in the future, know there are varying levels of oversight available; that is, guardianship is not the only answer. Below are factors to consider and alternatives that may be a better fit for your situation.

In this hypothetical situation, we’re referring to “Sam”, who has recently turned 18 and has developmental disabilities that affect his ability to care for himself fully and make major decisions on his own.

First, consider the hard questions:

- Is Sam able to fully manage his personal, medical & financial decisions?

- Could Sam be vulnerable to others?

- The situation: Sam is living at home with his family and is eligible for SSI benefits, but he hasn’t applied and since he’s now an adult, no one in his family is able to apply on his behalf.

-

- Sam spends money quickly and can often be too generous with

- Now that he is 18, school officials and his doctors will no longer speak to his parents without Sam’s permission.

-

- Sam is eligible for a driver’s license, but his family and doctors do not feel that he should be driving – as an adult, however, he does not need their permission.

What can you do as a parent or guardian to support Sam while also looking out for his best interests and keeping him safe?

- Consider alternatives to guardianship that focus specifically on the areas where he may need support, such as:

- SSA Payee for SSI/SSDI

- Joint Bank Account

- Signature Authority on Bank Account

- Advance Directives

- If Sam has the requisite mental capacity and can identify people he trusts to assist with decision making, then signing legal documents such as these may be an option for him.

- Advance Directives may include these powers of attorney:

- Financial Matters

- Health Care

- Educational Decisions

- Supported Decision Making arrangement

- Advance Directives may include these powers of attorney:

- Consider guardianship if the above alternatives do not provide the level of support required for the individual’s safety and If the individual is deemed by a court to lack sufficient capacity to manage his or her own affairs or make and communicate important decisions, then the court may give legal authority to a guardian to make decisions on behalf of the individual.

Obtaining guardianship is not easy, nor should it be. There are different types of guardianship, ranging from guardianship “over the person” (health, education, where to live), “over the estate” (money, contracts, etc.) and over both “person and estate”.

Who may serve as a guardian?

- Parents, siblings, relatives, friends

- Will your decision to proceed for guardianship affect your relationship with the individual?

- What if a family member is not the best option?

- An agency or private individual could serve as guardian

What powers will guardians have?

Guardianship order must be “least restrictive form of intervention”

- Limited in scope

- Designed to maintain the greatest amount of personal freedom and civil liberties for the individual (often called a “Ward”) consistent with their mental and physical limitations

If you’re considering any of the support options on this page, it is critical you carefully consider a number of complex factors. We highly recommend that you discuss your situation with an attorney experienced in these areas, as well as your child’s doctors, teachers, case managers, counselors, and other professionals with in-depth knowledge of your family and of the alternatives available.

Healthcare & Public Benefits

As your child nears age 18, another important area to re-examine is their public benefits picture. As an adult, your child may qualify for means-tested public benefits such as Supplemental Security Income (SSI) and Medicaid, since financial eligibility will be based on the child’s resources and income alone.

A Special Needs Trust (SNT) can provide for your child upon your death without affecting financial eligibility for essential public benefits that may be available. If you have not yet established an SNT, this is certainly something to consider.

If a child develops their disability prior to reaching the age of 22, they may be entitled to receive social security as well as Medicare based upon a parent’s work history.

Health Care Decisions

Medical information is subject to strict confidentiality rules, and once a patient turns 18, medical information is only provided to the patient. A patient may sign a release to allow family member(s) or other selected individual(s) to have access to protected health care information. Also, a patient may designate a family member, friend or interested person to make health care decisions for the patient as an agent under a health care power of attorney, but only at such a time that the patient becomes mentally unable to make his or her own medical decisions. If the patient does not have the mental capacity to sign a health care power of attorney, individuals could become the patient’s health care decision maker under the surrogacy or guardianship laws, as discussed above.

Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (“HIPAA”) Release

If an individual has the mental capacity to do so, a HIPAA release may be signed by such individual at age 18 to provide designated individual(s) access to confidential medical information. While medical information may be accessed through a review of medical records and/or direct communication with health care providers, an executed HIPAA release does not provide the designated individual with any decision making authority. A HIPAA release may be revoked at any time by the patient.

Funding for Daily and Long-Term Needs

Depending on your adult child’s needs, school status, and living situation, a number of supports may be available to assist with funding their daily and long-term needs. These may consist of one or more of the following:

Supplemental Security Income (SSI)

SSI is a federal cash assistance program for individuals 18 and older who meet certain income and resource standards and have a disability which is expected to last at least 12 months. An individual under the age of 18 also might be entitled to SSI, but this is uncommon because the parents’ income and resources are counted. The maximum cash benefit for an individual is published annually and the amount increases only if there is an annual cost of living increase. SSI is a complex program that measures a number of support sources, including an individual’s living situation and any in-kind support against a final benefit determination.

Special Needs Trusts (SNT’s)

Special needs trusts are designed to set aside funds to benefit a person with disabilities while still preserving eligibility for public benefits that are based on financial need, like SSI or Medicaid.

There are two general types of special needs trusts:

- Third-Party Special Needs Trusts are created by parents, grandparents or others, generally with the intend of holding an inheritance for an individual with These trusts may not contain assets that previously belonged to the individual/trust beneficiary.

- Self-Settled Special Needs Trusts are intended to hold the assets belonging to the individual/trust beneficiary. An example of this would be an adult who was deemed disabled after having earned assets and/or income during their life, an individual who received a personal injury settlement or an inheritance outright.

For more information on the different types of special needs trusts, see this article.

ABLE (Achieving a Better Life Experience) Accounts

ABLE is a federal law that allows a person with disabilities to own a tax-advantaged savings account. A person became disabled before age 26 is able to transfer funds to an ABLE account. Although assets held in an ABLE account belong to the individual with disabilities, the value of those assets are not counted when applying for a benefit program that has an asset limit, like Medicaid or Supplemental Security Income (SSI). Funds held in an ABLE account can be used to pay for the individual’s disability-related expenses, including food, shelter, therapy, and adaptive equipment or transportation.

ABLE Accounts vs SNT’s – Which Is Best For You?

There are advantages to both special needs trusts (SNTs) and ABLE accounts, and it is very possible both of these vehicles would benefit the same individual. In general, SNTs are not used to pay for food or housing because such distributions will be counted as “unearned income” for certain public benefits programs that have an income limit, such as Medicaid or Supplemental Security Income (SSI). In contrast, ABLE accounts can be used to purchase food or pay for housing without any effect on SSI and Medicaid income eligibility. On the other hand, there is a limit as to how much money may be contributed to an ABLE account on a yearly basis, which is not the case for SNTs, and SNTs can hold real estate, stocks and bonds, whereas ABLE accounts cannot. For these and other reasons, including how much money is involved, some individuals may find it beneficial to establish an ABLE account in place of, or in addition to, an SNT. Exploring these options with a knowledgeable attorney can help you arrive at the best decision for your unique situation.

Letter of Intent – What Is It and Why Is It Important?

Once families have finalized their estate plan by creating a special needs trust to ensure eligibility for public benefits is preserved, and selecting a capable trustee to manage their loved one’s assets or inheritance, what else is needed? The answer perhaps is one of the most important pieces of transition planning – not a formal legal document, but something much more personal—a “letter of intent.” A letter of intent is focused on the personal preferences and needs of an individual, going beyond the mechanisms of asset preservation and distribution to address the “what” and “how” of supporting and promoting your child’s quality of life and overall well-being.

As such, a letter of intent is a unique and personal planning document. It is created to capture what you, as parents, know best about caring for your child and their likes, dislikes, and preferences. A written letter of intent is a valuable document at any stage of life for individuals with intellectual or developmental disability, but it takes on significant importance during a major transition period such as the move from school to adult life.

When it comes to creating a letter of intent, no detail is too small. Think of a typical day and all the various activities it encompasses. The objective is to equip any future caregiving team with all the information you can to minimize the inevitable disruption and distress your child will experience when you are not there. Understandably, the process of writing a letter of intent is difficult and emotionally challenging for parents or caregivers, but by serving as a knowledgeable blueprint for those who will care for your child in the future, it simply is invaluable. A letter of intent also will allow you to give any future caregiving team the gift of truly seeing your child through your eyes.

Even if you have already gone through the process of writing a letter of intent, it’s important to thoroughly review and update it during transition planning, as you will likely find that your child’s needs, wants, interests, and even the people involved in key decisions, have changed over the years.

Resources & Next Steps

Working with your child to plan for transition from school supports into adulthood will be one of the most important things you do for them as a parent or guardian. Don’t go it alone. Your child’s school and other community resources can help you chart a path forward with meaningful, attainable goals to make the transition to adulthood and out of the school system a successful one. When it comes to the broad range of legal and financial questions to be considered when devising the best plan for your child’s life as an adult, consulting an attorney experienced in special needs planning is another invaluable tool.

Here are a few resources that may help you along the way:

- ABLE Act – overview and details

- Education & Career

- Legal – Special Needs Planning, SSI/SSDI, Medicare/Medicaid, and Estate Planning